©Philip Sinden

©Philip Sinden

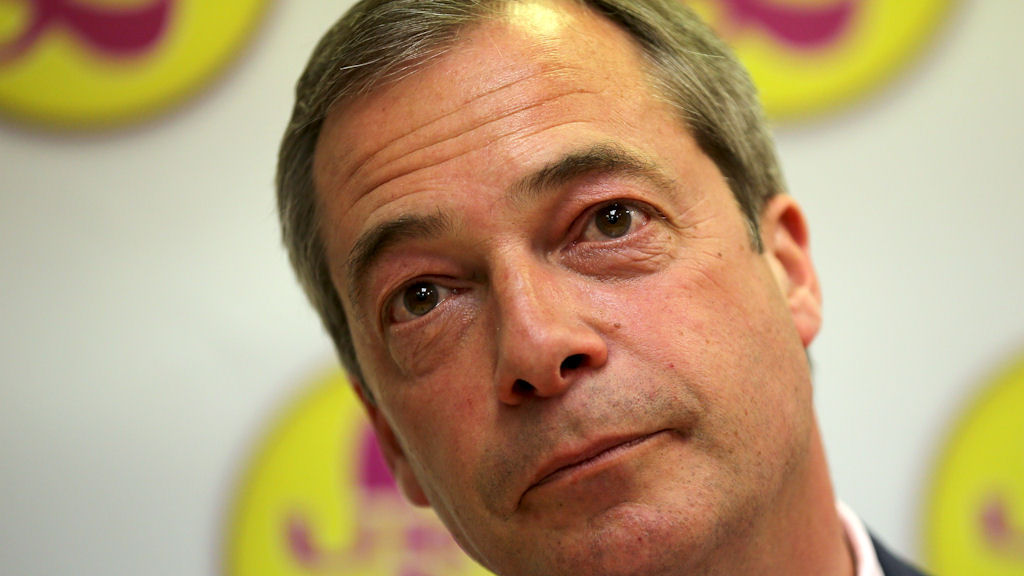

On election day May 6 2010, a man in a pinstriped suit boarded a light aircraft at Hinton-in-the-Hedges, Northamptonshire. Trailing on the dewy grass was a banner bearing a forlorn last-minute appeal: “Vote for Your Country – Vote UKIP.” Hardly anyone bothered to turn up.

While the world focused on a grey-faced Gordon Brown’s desperate fight to cling to power and on David Cameron confidently preparing for Downing St, the plane began its ascent over the English countryside. Within minutes, it was clear something was badly wrong: the banner was wrapped around the aircraft’s tail and rudder.

Nigel Farage’s relentlessly upbeat demeanour suddenly changes. “I thought: this is probably it,” he says. What does he remember? “The noise. The noise of the nose hitting the ground. Bang! I can still hear that.” His voice cracks.

More

ON THIS TOPIC

IN FT MAGAZINE

“I barely want to think about it but I was upside down, completely caved in. I could hardly breathe, I was covered in fuel oil. I was desperate to get out … desperate. I kept pushing … I couldn’t get out. I thought, this thing is going to catch fire. Very scary. I promise you – that is very, very scary.”

This is Farage, leader of the UK Independence party, as you never see him. The heavy-smoking, beer-drinking maverick – scourge of Brussels and terror of Britain’s political elite – is a man lodged in the public consciousness as a jovial insurgent, dispensing barroom wisdom with remorseless good cheer.

But there is another side to Farage. The man pulled from the wreckage – sternum split, lung punctured, 10 bones broken, rosette slightly askew – emerged with a new-found purpose. Behind the jokey façade is a man with a deadly serious intent: to smash open the British political system and lead theUK out of the European Union.

“I think the accident made him more ruthless and more single-minded,” says David Campbell Bannerman, a former Ukip deputy leader. The British public and an increasingly anxious political elite across Europe are now starting to ask: “Where did Nigel Farage come from and where is he heading?”

©Philip Sinden

©Philip Sinden

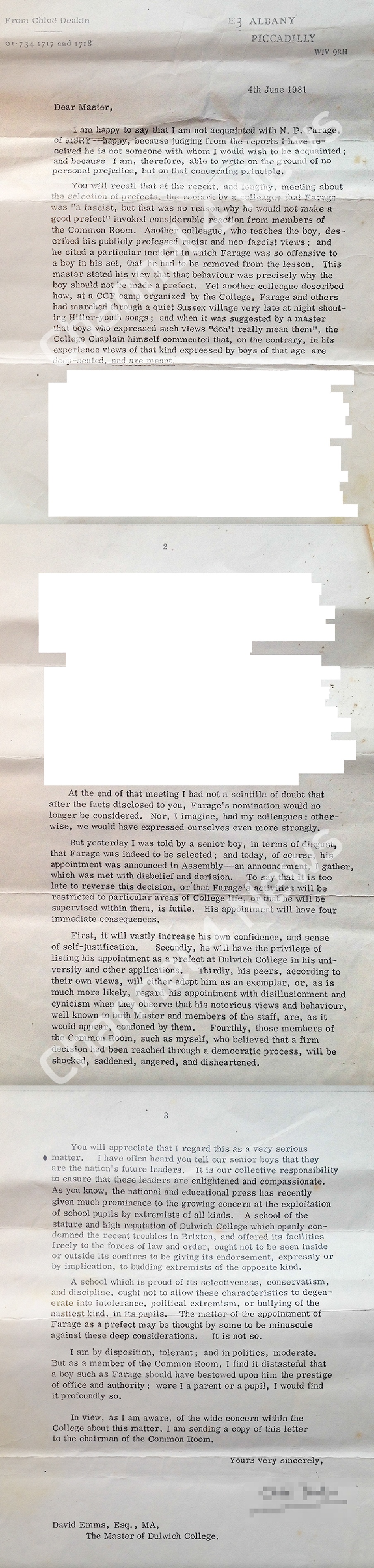

Although Ukip has been around for 20 years and won 13 seats in the last European elections, the party’s rise under Farage’s leadership has been remarkable.

When Farage fell from the Northamptonshire skies on polling day in 2010, the crash was little more than a footnote in the general election. Ukip polled a modest 3 per cent and Farage’s own attempt to oust the House of Commons Speaker John Bercow in his Buckingham seat was a conspicuous failure: he was even beaten into third place by a strongly pro-European independent candidate. For many, the crumpled figure hauled out of the wreckage that morning was already a busted flush.

Less than three years later, and Farage is revelling in his party’s best-ever result in a parliamentary election. Ukip did not win the Eastleigh by-election, but it would be hard to tell from the demeanour of the party leader as he swaggers through a crowd of well-wishers amid a sea of lurid purple banners in the faded town centre.

The contest confirmed that Ukip under Farage is becoming a serious force, shearing off support from Cameron’s Tories but also claiming that two-thirds of its Eastleigh vote came from former Labour and Liberal Democrat supporters and previous non-voters.

A party supposedly comprised of “cranks, gadflies and extremists” – in the words of former Tory leader Michael Howard – fielded an articulate healthcare specialist, Diane James, as its candidate. James came second to the Lib Dems with 28 per cent of the vote; most agreed that if the campaign had lasted another week she would have won.

©Getty

©Getty

Celebrating with Ukip candidate Diane James at the Eastleigh by-election, February 28; James beat the Tories to take second place

“We will take this tremor in Eastleigh and turn it into a national earthquake,” says Farage (it rhymes with “barrage”) in his clipped, military tones. But already his party has shaken the political establishment and forced Cameron’s Conservatives – fearing a fatal schism on the political right – to start engaging Ukip on its chosen battleground: Europe and immigration.

. . .

The 48-year-old man pulling the strings has other things on his mind when we meet in an Italian café in Westminster. Heavy bags under his eyes, he is drained by a schedule that takes him between “that dump” Brussels (where he works as an MEP) and Britain, where he lives in the Olde England Kentish village of Downe.

“I caught up with the post at midnight last night,” he says. “Fines for this, fines for that. If I don’t do my tax return they’re going to put me in jail.” Such is Farage’s dominance of his party (no other Ukip member comes close to his profile) he is in heavy demand from media across Europe. “On the day of Cameron’s Europe speech I did 16 hours of broadcasts,” he says. Campbell Bannerman – who left Ukip to become a Tory MEP – says Farage recognises he has become “a cult”.

©INS News Agency Ltd

©INS News Agency Ltd

Farage in the wreckage

“There’s no escape … no escape,” Farage says. “I’m generally a pretty ebullient, optimistic person. I try to enjoy life, but are there just little times when you think, ahhh? Of course there are. No human being can work the number of hours I do a week and not have the odd moment like that.”

Nigel Paul Farage was born in Kent in 1964, one of two sons of a colourful and hard-drinking City stockbroker. Guy Justus Oscar Farage’s propensity to mix work with pleasure was clearly influential on the young Nigel, who followed his father into the City as a highly remunerated commodities trader. (Andrew, Farage’s younger brother, also headed to the City, where he still works as a broker on the London Metal Exchange.)

Guy, who became an alcoholic, divorced his wife Barbara when Nigel was five. But Farage acknowledges his father’s influence: like Guy – “the best-dressed man in the stock exchange at the time” – Nigel bears the demeanour and attire of a City gent before the barbarians were allowed in after the 1986 “Big Bang” reforms.

©INS News Agency Ltd

©INS News Agency Ltd

Farage after his airplane accident, May 6 2010

The sense of nostalgia for a bygone age was summed up by the story of when Guy – who kicked the bottle in his mid-thirties – was in the lift with Sir Nicholas Goodison, chairman of the London Stock Exchange, at the time of Big Bang and lamented, “You’ve ruined the best gentleman’s club in the world.”

In spite of his father, Farage enjoys a pint, using his local, the George & Dragon, as a testing ground for Ukip policies: “In my village pub they are totally against,” he says of Cameron’s plan to legalise gay marriage. To complete the anti-politician image, Farage is a heavy consumer of Rothmans cigarettes and enjoys sea-fishing and country sports. A Barbour-clad Farage loves cricket and used to be seen enjoying hare coursing – until it was banned in 2005. In short, he is a young-ish fogey: most people are surprised to learn he is still in his forties.

Farage is also a walking health-insurance nightmare. After leaving the prestigious Dulwich College in south London – alma mater of P.G. Wodehouse – and embarking on his City career he was knocked down by a car, aged 21, on his way home from a pub argument about UK-Irish relations – heavily lubricated by Irish whiskey and English ale.

Lucky to survive, he was only just emerging from a year in half-plaster when he was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Farage has expressed his “gratitude to evolution” for providing him with a spare: he has gone on to father four children in the course of two marriages. Given his track record, it was perhaps no surprise to see him staggering out of a crashed plane.

©Getty

©Getty

Traders at the London Stock Exchange in 1984; Farage followed his father into the City before taking up politics

In spite of his success in the “trench warfare” of commodities trading – a lifestyle punctuated by spread betting and drinking – by the early 1990s Farage was becoming increasingly political. He feared that the traditional British way of life he cherished was in some way under threat from a European project whose ambitions were expanding rapidly.

His opposition to the EU crystallised as Britain dabbled with what he regarded as the lunacy of the Exchange Rate Mechanism – the precursor to the euro. The Maastricht treaty of 1992, which paved the way for a much closer union and the creation of the single currency, radicalised him.

But Farage was very different from most of the other founder members of Ukip in the early 1990s. He was young for a start and had an internationalist outlook. After divorcing Clare Hayes in 1997 (the couple had two boys, Sam and Tom) Farage married a German government bond broker, Kirsten Mehr, with whom he has two girls, Victoria and Isabelle. He had an agency business in Milan and worked for two French companies. By contrast, his new colleagues had personal memories of when a real military threat came from across the Channel: “You could always tell a Ukip meeting by the number of Bomber Command ties,” he says.

Articulate and media-savvy – Farage likes to hold press briefings in pubs – he quickly rose through the party. By 1999 he was an MEP and in 2006 he was elected party leader. Although he briefly quit as Ukip leader in 2009 to contest the Buckingham seat – he said he was fed up with being “head cook and bottle washer” – he was back a year later. A remarkable renaissance was now under way.

The crisis in the eurozone fuelled Ukip’s rise, as did a sense that Britain lost control of its borders in the past decade when hundreds of thousands of Poles and Lithuanians came to the UK. But polling suggests that Farage is primarily surfing a wave of hostility towards all mainstream politicians: Ukip has become Britain’s protest party of choice.

The most dramatic consequence of Ukip’s growing popularity was Cameron’s decision in January to offer a British referendum on EU membership in 2017, if he wins the next election. The move was intended to halt the Farage surge, but for now at least it seems to have had the opposite effect. “They’re coming to play on our pitch now,” Farage says.

In Eastleigh, Farage proved he could combine his anti-EU message with a more visceral campaign against mass immigration. He claims that Europe’s free movement rules will lead to a mass influx of Romanian and Bulgarian migrants next year when travel restrictions are lifted.

Ukip has other radical – some would say ludicrously unaffordable – policies to cut taxes and increase spending on the police, prisons and army, but the public is barely aware of them: Europe and immigration are Ukip’s greatest hits. Farage makes immigration sound like it is the most pressing issue facing Britain and the message is resonating.

“I moved out of Southampton because you had a job to hear English being spoken,” says Stuart Wellstead, a handyman living in a cul-de-sac in the Eastleigh suburbs. “I can’t understand why we have an open-door policy when so many of our own are unemployed.”

Cameron and Labour’s Ed Miliband have inexorably been drawn on to policy terrain where Farage knows he is invincible: while mainstream politicians cannot rip up Europe’s commitment to the free movement of workers, the Ukip boss can offer voters like Wellstead the simple expedient of leaving the EU altogether.

After Eastleigh, Cameron insisted he would not desert the centre ground, but his team spent the next few days talking about Britain pulling out of the European Convention on Human Rights and taking measures to stop “benefit tourism” by Romanian and Bulgarian migrants.

“They’re all at sea,” Farage says as he surveys the post-election fallout. “They are just being blown around by the wind. They’re more split than they’ve ever been and the problem is that nobody in his party believes Cameron any more.”

One Tory minister admits Ukip is already having a profound effect on British politics without having a single seat in the Commons. “It’s like the Green party in the 1990s – they ended up greening all the major parties and Ukip could have the same effect on issues like Europe and immigration.” Critics would say that Farage’s influence is malign and mean-spirited; he says he is only speaking up for the people.

The arrival of Ukip in 1999 at the European parliament was a culture shock to say the least. Ukip brought a penchant for banners, occasional public protests and rare flashes of passion to the sterile European parliament hemicycle. When Tony Blair came to the parliament in Brussels, Farage and his Ukip colleagues taunted him from their seats, festooned with Union Jack flags. The anger flashed across Blair’s eyes: “This is 2005, not 1945. We are not fighting each other any more.”

Farage says a defining moment for him came in 2005. He was drinking champagne in the Brussels press bar to celebrate the Dutch rejecting the EU constitution in a referendum when a German MEP came by and said, “You may have your little celebration tonight but we have 50 different ways to win.” I thought, ‘My God, these people are frightening, they’re fanatical.’”

. . .

In 2009 Britain returned 13 Ukip MEPs – the party finished second – and Farage became the leader in Brussels of a group of rightwing European parties which shared his desire to throw sand in the wheels of the EU. But with increased success came increased scrutiny of Farage; was he the jolly frontman for a movement with a less savoury side?

Ukip describes itself as a “democratic libertarian party” opposed to discrimination of any kind, but it is part of the Europe of Freedom and Democracy group that includes the Italian Northern League, some of whose members have expressed sympathy with the extreme racist views of Norwegian mass-murderer Anders Breivik.

The Northern League’s Mario Borghezio declared in a radio interview that Breivik had “excellent” ideas, remarks which Farage condemned. Meanwhile Ján Slota, leader of the Slovak National Party, Ukip’s Slovak allies, has railed against his country’s Hungarian minority as a “tumour” and suggested dealing with Roma with a “long whip in a small yard”.

Farage rejects forcefully any suggestion his party is racist and points out that it does not allow any former BNP members to join (a proscription that is not applied by other mainstream British parties). This ban is on one level a defensive measure: Ukip fears that the shambolic BNP will try to reassemble under the Ukip banner through a policy of entryism.

Ukip’s members are at times famously politically incorrect, some would say misogynist. Ukip MEP Godfrey Bloom once quipped that “no employer with a brain in the right place would employ a young, single, free woman”, while Marta Andreasen (the party’s only woman MEP) last month defected to the Tories claiming Farage was “an anti-woman Stalinist dictator”.

Farage chuckles at the idea that he does not like women. In 2006 he drunkenly suspended his hostility to the EU’s open borders policy to accept an invitation for a late-night drink from a “sleek and seductive” 25-year-old Latvian called Lita.

Lita told the News of the World that Farage was something of a stud and that they had had sex seven times before he fell asleep, “snoring like a horse”. Farage, in his memoirs, Flying Free, claims he was too drunk to perform, although he concedes the snoring. “Lita wasn’t screwed. I was.” He was in “fearful trouble” with Kirsten, but the master of unlikely escapes survived with his marriage intact.

Polling shows Ukip’s abrasive message – anti-immigration, anti-Europe, anti-wind farms – appeals more to men than to women, but Farage angrily rejects suggestions that his party is an expression of the male midlife crisis: a party yearning for the past and railing against uncontrollable external forces.

The selection of Diane James as Ukip’s candidate in Eastleigh is hailed by Farage as evidence that the party is broadening its base, and Farage describes as “moronic” the portrayal of his party as a bunch of be-blazered men drinking in the 19th hole. “Actually we’re picking up quite a lot of support from cool, trendy youngsters, who view Europe as an anachronism,” he says.

The party has seen questions raised about its funding arrangements. Some of his MEPs have run into trouble for expenses irregularities: indeed, a lot of Ukip’s money comes from the legitimate expenses payable to its dozen MEPs. Farage said in 2009 he reckoned he had received “pushing £2m” from the taxpayer over the previous decade. Farage also runs an office in London from the headquarters of the European Commission – ironically Margaret Thatcher’s former HQ in Smith Square – joking that he “takes the devil’s money to do the Lord’s work”.

Ukip was almost ruined after it received a £367,000 “impermissible” donation from former bookmaker Alan Bown – “honest Al” as Farage calls him – after it transpired that he was not on the electoral register when he handed over the cash. Only an appeal to the Supreme Court in 2010 spared the party from having to pay the money back.

The party received donations of £314,000 last year from 66 sources – roughly 2 per cent of the money donated to Cameron’s Conservatives – including from Lord Pearson, a former Ukip leader and insurance man.

Stuart Wheeler, founder of the spread betting company IG Index, has also bankrolled the party. It has just nine staff in its central operation.

Ukip’s recent success – it is regularly scoring 10 per cent in national opinion polls – has brought new pressure to bear on Farage. A party that attracted eccentrics and the politically incorrect is now starting to lay down the law to those who bring the party into disrepute.

©AFP

©AFP

Speaking in France last year. On his home turf, the 'media-savvy' Farage likes to hold press briefings in pubs

Andreasen, who quit Ukip in a dispute over candidate selection, claims Farage is “desperate to control things” and surrounds himself with yes men, adding: “Either he gets what he wants or you’re out.” Farage has shrugged off the attacks, noting that Andreasen, a former EU chief accountant, has made a habit of acrimonious departures from various organisations.

The party has acted to remove a local Ukip chairman for waging “a war against homosexuals” and, more recently, the leader of the party’s youth wing for saying he backed gay marriage and wanted to legalise drugs in breach of party policy. As it grows, the party’s constitutional commitment to “libertarianism” seems to be waning.

“I don’t want us all to agree,” says Farage. “But here’s my problem: on the one hand I want us to take a traditional, liberal approach to politics and debate where we do feel free to say what we think, but on the other I can’t have people bringing the whole thing into disrepute.”

Campbell Bannerman says that as Ukip becomes more like other political parties, Farage will struggle because “he doesn’t like policy, he doesn’t like detail”. But Farage rejects the idea that he is some kind of dictator. “I wish I was more of one really,” he says. “I don’t think I’m as tough as I ought to be.”

. . .

Farage acknowledges that the party is experiencing growing pains. He says there is a “lot of catching up to do” as Ukip tries to match its threadbare central organisation with its burgeoning national support, but says he has talented people around him – like Stuart Wheeler and Steve Crowther, the party chairman – to handle the day-to-day running of the party. He focuses on the “politics, media and helping with fundraising”.

There are certainly plenty of potential problems ahead if Ukip continues to grow, but those problems are for the future. For David Cameron and Britain’s other mainstream politicians, Farage poses a clear and present danger.

With Sophie Raworth on The Andrew Marr Show, March 3

The challenge is to work out what the danger is. Pollsters analysing Ukip’s surge from 3.5 per cent in Eastleigh in 2010 to 28 per cent this month – or indeed its national ascendancy – tend to agree on one thing: it has relatively little to do with the public’s hostility to Europe, an issue which never makes the top 10 of their daily concerns.

Lord Ashcroft, the Conservative business tycoon and pollster, has urged Cameron to keep calm and not pander to the Farage agenda. He argues that voters in Eastleigh know the difference between a by-election protest and the choice of a government in a general election.

Ashcroft expects Ukip to fade in the 2015 poll (when Britain’s first-past-the-post voting system discriminates against smaller parties), just as it did in the 2005 and 2010 elections.

In an extensive piece of research, Ashcroft says Farage and his party appeal because of their general outlook. “Certainly, those who are attracted to Ukip are more preoccupied than most with immigration, and will occasionally complain about Britain’s contribution to the EU or the international aid budget,” he wrote.

“But these are often part of a greater dissatisfaction with the way they see things going in Britain: schools, they say, can’t hold Nativity plays or harvest festivals any more; you can’t fly a flag of St George any more; you can’t call Christmas Christmas any more; you won’t be promoted in the police force unless you’re from a minority; you can’t wear an England shirt on the bus; you won’t get social housing unless you’re an immigrant; you can’t speak up about these things because you’ll be called a racist; you can’t even smack your children.”

Ashcroft concluded after Eastleigh that Cameron could best tackle Farage’s insurgency by proving that a mainstream Tory government could improve the quality of people’s day-to-day lives. “Our task is not to become more like Ukip, the party of easy answers, but to be the party of government that people want to vote for.”

Cameron’s problem is that many Tory MPs can see their chances of election victory in 2015 disappearing and are pushing him to the right – partly for self-serving reasons – to try to neutralise the Ukip threat.

Tory and Labour nerves could be shredded come next year if – as Farage hopes – Ukip win the 2014 European elections, only a year before the next general election. Many at Westminster now believe it is only a matter of time before Labour and the Liberal Democrats are forced to match Cameron’s promise of an EU referendum.

Won’t that make Ukip irrelevant? Farage says that successive hardline Tory leaders have promised to get tough on Europe and each time he has been told his party would be obliterated. “I’ve heard this before,” he says. “Do I trust Cameron? No.”

In any event, Farage’s uncanny ability to articulate Britain’s 21st-century concerns suggests he will remain a big factor in the next election. Some compare him to Alex Salmond, the Scottish Nationalist leader, who has channelled patriotism and a desire to break free from the dominance of “the other”. Farage says he hopes he has some of Salmond’s ability to “speak a language that ordinary folk understand”.

After Eastleigh some Tory MPs believed they had found a chink in Farage’s bulletproof political persona. If Farage had stood, they claimed, he might well have won the seat. “Farage bottled it,” says George Eustice, a Tory MP. Andreasen claims he has grown to love the life in Brussels he professes to despise and does not really want to win a seat at Westminster.

Farage is getting used to the barbs but sounds like he is digging in for the long haul. Can Ukip win seats in the House of Commons? “It’s not guaranteed, because we’ve got a hell of a long way to go. And we’re going to need some senior figures to come and help us do that.”

But you can never be sure with Farage. After his surprise resignation as Ukip leader in 2009, he was persuaded only with some reluctance to come back to the top job after his brush with death at Hinton-in-the-Hedges.

“If I was honest, on a personal level, all of this has come at a massive sacrifice,” he says, staring into his Italian coffee. “The financial sacrifice has been huge. Many of my colleagues from the late 1980s are now extremely rich people and I don’t mean comfortably off, I mean extremely rich people.”

He pauses. “If I’d concentrated on business I would have been a very wealthy man. Do I mind that? No, I chose it. But I think the sacrifice of time, the complete lack of time for family and any sense of normality, that is a sacrifice. I’m not whingeing because I chose it, but it gets a bit wearing. And I did walk away from it once, remember.”

~~~~~~~~~~#########~~~~~~~~~~